Memory Overhead of Lua Coroutines

Lately I’ve been working on adding NPCs to Sovereign Engine. Sovereign uses Lua 5.4 for server-side scripting, and after playing around with behavior scripts for a while, I’ve settled on a design I like based around Lua coroutines. Essentially, each entity behavior is defined by a Lua script which attaches to an entity (such as an NPC) when it is loaded and creates a new coroutine for that entity. For example, the behavior script for a wandering NPC looks something like this:

local EntityBehavior = require('EntityBehavior')

-- ...

EntityBehavior.Create(

function (behavior, entityId)

-- Retrieve the per-entity movement parameters.

-- ...

while true do

-- Wait until time to move again.

behavior:WaitAsync(entityId, delayTime)

-- Start movement.

local direction = PickRandomDirection()

local posVel = components.kinematics.Get(entityId)

posVel.Velocity = VelocityInDirection(speed, direction)

components.kinematics.Set(entityId, posVel)

-- Wait until movement done.

behavior:WaitAsync(entityId, moveTime)

-- Stop movement.

posVel = components.kinematics.Get(entityId)

posVel.Velocity.X = 0.0

posVel.Velocity.Y = 0.0

components.kinematics.Set(entityId, posVel)

end

end

):InstallGlobalHooks()

Here, an anonymous behavior function is being wrapped by the EntityBehavior class. EntityBehavior manages a pool of coroutines, one per loaded entity with this behavior, all executing the behavior function concurrently. Since these are coroutines rather than threads, the per-entity behaviors are not executing in parallel; rather, the execution context is swapped in and out as the coroutines yield (at the behavior:WaitAsync calls). As long as the time between subsequent yields is short, Sovereign’s scripting engine can rapidly execute the behaviors of large numbers of entities. As an added bonus, the behavior functions are easy to read and write - no need to think about switching between multiple entities or handling callbacks, as the coroutine infrastructure provided by the engine and EntityBehavior handle that transparently to the developer.

The benefits of the coroutine-based approach come with a tradeoff. If each dynamic entity loaded by the server has its own coroutine, then the scripting engine needs to maintain a separate execution context (a Lua “thread”) for each entity. As Sovereign is designed to handle hundreds of thousands to millions of concurrently loaded entities, these tradeoffs need to be understood and considered carefully. I spent some time searching on Google for information on the memory overhead of Lua coroutines, but I wasn’t able to find much information.

That means it’s time to build a benchmark.

Benchmark Methodology

I wanted to create a benchmark for Lua 5.4’s memory overhead with large pools of coroutines. The goal is to understand how much memory is allocated by coroutine pools of various sizes, and from this determine the amortized per-coroutine memory overhead at the millions-of-coroutines scale at which Sovereign operates.

I started by designing a simple benchmark script that could spawn large pools of coroutines:

local unistd = require('posix.unistd')

-- write PID to file at startup

local pid = tostring(unistd.getpid())

local f = io.open('pid', 'w')

f:write(pid)

f:close()

function myRoutine()

coroutine.yield()

end

-- allocate coroutines

local coros = {}

-- read integer from command line argument

local n = tonumber(arg[1]) or 0

for i = 1, n do

local co = coroutine.create(myRoutine)

coroutine.resume(co)

table.insert(coros, co)

end

collectgarbage("collect")

f = io.open('ready', 'w')

f:write(1)

f:close()

while true do

unistd.sleep(1)

end

Let’s break down what is happening here:

- The benchmark process’ PID is written to a file. This is used to orchestrate the benchmark (discussed shortly).

- A simple coroutine function

myRoutine()is defined. This function immediately yields on entry, thereby minimizing any overhead on the coroutine’s stack while also ensuring that Lua can’t perform any cleanup of a completed/returned coroutine. - A large number of coroutines are created and resumed with the

myRoutine()function as their entry point. The resulting Lua threads are accumulated in a table. On each iteration, the execution context switches to the coroutine thread at the start ofmyRoutine(), which immediately yields and returns to the original context. - Garbage collection is manually triggered. In a long-running script (such as a Sovereign behavior script), this would happen naturally over time. Here we trigger it manually to achieve the same effect in a reproducible and controllable way.

- A sigil file is created. Like with the PID file in the first step, this is used to orchestrate the benchmark.

- The script enters a busy loop repeatedly calling sleep. This keeps the Lua process alive but quiet to permit measurement of its memory usage.

Next, I needed a way to automatically run this script and gather the results:

#!/bin/bash

eval "$(luarocks path --bin)"

CSV="results_$(date +%Y%m%d_%H%M%S).csv"

: > "$CSV"

echo "N,VmRssKb" >> "$CSV"

for ((exp=4; exp<=23; exp++)); do

N=$((2**exp))

rm -f pid ready

lua CoroutineOverhead.lua $N &

while [ ! -f ready ]; do sleep 0.1; done

PID=$(cat pid)

VmRSS=$(grep VmRSS /proc/$PID/status | awk '{print $2}')

echo "$N,$VmRSS" >> "$CSV"

kill $PID 2>/dev/null

wait $!

done

Once again, let’s break down what is happening here:

- The sample size is iterated, in powers of 2, from 16 through 8388608 coroutines.

- For each sample size, we remove the

pidandreadyfiles, then run our Lua script in the background. - The script waits until the

readysigil file is created by the script. - The Lua process’ pid is read from the

pidfile, and this is used to retrieve the RSS (resident set size, or the amount of physical memory committed to the process). - The sample is appended to a CSV file and the Lua background process is killed.

Results and Discussion

I ran the benchmark on my older development PC with Arch Linux, 32 GB of physical RAM, and no swap space. The Lua interpreter was the stock Lua 5.4 shipped with Arch (at the time of writing, that is the lua 5.4.8-2 package).

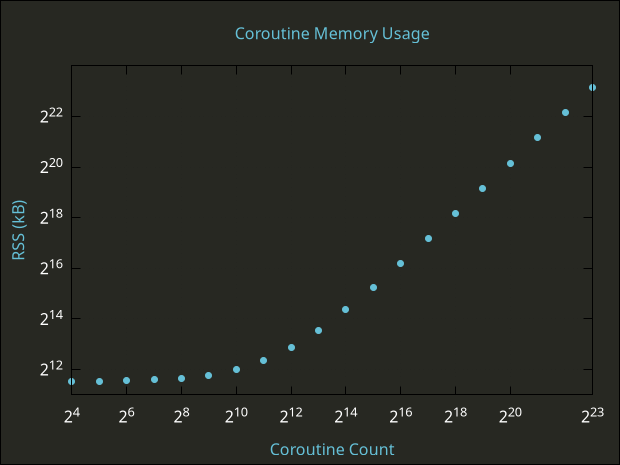

Total Lua memory usage for benchmark as function of number of coroutines.

The plot of memory usage vs coroutine count looks like what I expected: a relatively flat region where the overhead of the Lua process dominates, followed by a region of linear growth that probably continues indefinitely toward the asymptotic limit. The transition into linear scaling occurs roughly in the vicinity of 2048 coroutines. I suspect that Lua is allocating a few megabytes of working memory right away and making this available to scripts, then beginning to allocate larger blocks at a linear rate once a certain usage threshold is crossed.

At the benchmark’s upper limit of \( 2^{23} \) coroutines, the Lua process used an average of 9309046 \( \pm \) 57 kB (99% CL, 32 samples), or approximately 1.11 kB per coroutine. We can use this value as an approximate lower bound on the memory overhead per coroutine. So, as a rough rule of thumb, coroutine-based behavior carries with it 1 GB of memory overhead per million dynamic entities in Sovereign Engine. From a memory overhead perspective, this is a viable approach to entity behavior at Sovereign’s target scale.

As a final note, the 1.11 kB of per-coroutine overhead assumes that the Lua library is compiled using the standard build options used by the Arch Linux build. It may be possible to reduce this overhead further by fine-tuning the build options and using a custom Lua build, for example by redefining LUA_FLOAT_TYPE in luaconf.h to use 32-bit floats instead of 64-bit doubles. However, the default per-coroutine overhead is low enough that this fine-tuning is not likely necessary for Sovereign Engine.

The source code for this benchmark is available on GitHub. If you found this interesting, you might also be interested in my personal project Sovereign Engine - an open source 2.5D multiplayer RPG engine which includes a powerful Lua-based scripting engine. To discuss this post, join our Discord.

AI Disclaimer

Generative AI (GPT 4.1) was used in this post for the purpose of writing boilerplate benchmark code and for generating the gnuplot input file for the memory usage plot. The benchmarks were not designed using input or suggestions from AI. No generative AI was used for writing in this post or for any other purpose other than the two cases stated above.